This guest post is from Ellie Lathbridge, Marketing Executive with JCS Online Resources, our K12 partner in Europe. Originally posted on LinkedIn, we’re republishing it here with her permission. Be sure to check out her other article on using manga to increase boys’ literacy rates.

My name’s Ellie and I’m autistic.

I often find that it comes as a shock to people who know me casually, but not at all to those who know me professionally or personally. When I was diagnosed in my late teenage years, my life started to make sense.

Autism: hard things are simple; simple things are hard

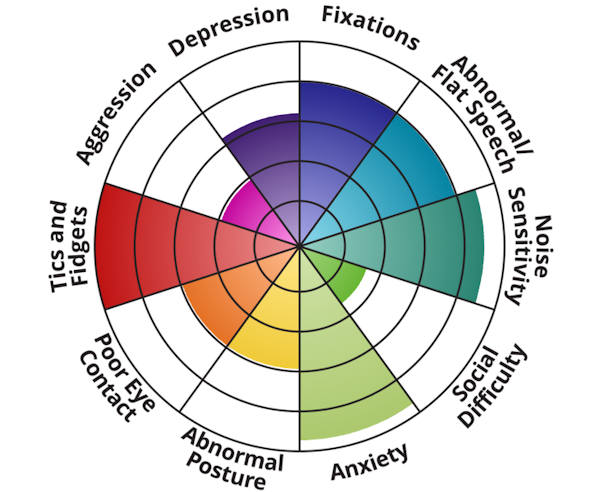

Meeting one autistic person means you’ve met one autistic person. ASD (autism spectrum disorder) is often characterised by having a ‘spiky profile’, i.e. the difference between my strengths and weaknesses is often more dramatic than my neurotypical counterparts.

I can repeat whole episodes of certain TV shows word-perfectly, but can’t tie my shoes properly. Research for 12 hours straight in foreign languages, but can struggle to process a casual spoken conversation in English.

And the kicker: I have two degrees in Languages and Literature, but cannot – for the life of me – finish a traditional book, especially fiction.

During my postgrad at Oxford, I was around a lot of ‘quirky’ people like me. Being in this bubble with many eccentrics who seemed to have similar struggles and challenges with spiky profiles made me feel normal. Outside of it? Not so much.

My reading experiences

Traditional fiction exhausts my brain

A misconception is that divergent readers have an issue with how complicated texts are from a technical standpoint. In my case, this isn’t the issue.

- Fiction is about relating to imaginary characters and worlds, something I find difficult without reference.

- I often miss plot points that seem obvious to others.

- The abundance of figurative language is something that can really confuse me sometimes. Either that, or I can begin to over-analyse it, as if I’m preparing for an exam question.

And when I say struggle, it’s not that I can’t do it, it’s that it is work. I get exhausted and it really impedes enjoyment.

Non-fiction, however, comes loaded with facts (often related to my special interests), diagrams and illustrations. From a technical standpoint, the non-fiction that I read is longer and way more complex than the fiction I struggle with, but my brain has an easier time.

It’s always been this way for me, but I wasn’t self conscious about it until my Year 5 teacher spoke to me when I brought in another non-fiction book for the 6th week in a row.

“You need to stop just reading encyclopedias. Why not look at the books the other girls are bringing in for some ideas?”

Immediate shame. I went from being excited to show off my latest reads to suddenly aware that I was standing out in a bad way. “You do read other books, don’t you?” I remember him continuing. I lied. “Yes, I just like bringing in the encyclopedias to show my friends.”

From then on, I started lying in my reading journal and grabbing whatever I had spare on my bookshelf to bring in for reading lessons.

By the time I had started high school, I still wasn’t reading fiction for pleasure outside two types: fanfiction (cleverly loaded onto my kindle) and manga series that I found online. I also simply kept on lying in my reading journal.

And as I got to university, people stopped checking that I was reading for pleasure. Don’t get me wrong, I’d read all the time for my degree. Journals, ancient poetry, academic book chapters. But it was for work, not for enjoyment.

And I had never liked actual reading, remember?

A route back to visual literature

When I first started my position as a Marketing Executive at JCS Online Resources in 2022, I was told I’d be launching a digital library called Comics Plus (by LibraryPass) for schools in the new year. Daunting to be told in your first week? Yes. Exciting? Absolutely.

Not only did it have a great selection of graphic novels and comics, it also had one of the most impressive digital manga collections I’d seen. And, you see, I loved manga as a teenager.

The first series that hooked me as an adolescent was Lovely Complex (ラブ★コン) by Aya Nakahara. I found myself being able to really relate to the characters and, because it was so visual and had an anime adaptation where I could easily assign voices and mannerisms to the characters, it was easy for me to read.

Looking back on my reading challenges, it makes more sense with the context of my autism. No wonder I was drawn to visual literature; there are no walls of text to get stuck on. Less reliance on beautiful, yet discombobulating, descriptive metaphors. The pictures do so much heavy lifting in relation to my issues: the worlds are visualised clearly, and the characters’ expressions are made more evident. I can just sit back, read, and enjoy.

These stories are also more likely to be aligned with my special interests, like pop culture, sci-fi, and fantasy. There are even quite a few titles about the experiences of neurodivergent individuals — who, it turns out, create a lot of visual literature.

What happened when I started reading visual literature again

As a teenager, I really needed Comics Plus or something similar: a digital library that championed manga, comics and graphic novels as valid forms of reading. An educational resource that showed that visual literature deserved respect and representation in libraries.

The more research I did for my job into why visual literature is so important, especially for many neurodivergent individuals or those who simply struggle with traditional books, the less shame I felt about my reading preferences as a teenager.

I realised I had always loved reading; I hadn’t loved the judgement about what I was choosing to read.

Where I am now

So far, in 2024, I’ve read over 60 fiction books. They’ve all been manga and graphic novels. I’ve also tackled a few historical linguistics encyclopedias. Sorry to my Year 5 teacher!

I’m proud to say that I love reading. I’m proud that my reading is visual literature. I’m proud that I can actually finish stories. And I’m proud to be an adult spreading the word about the importance of visual literature for younger readers.

How can you support those who struggle with reading

Educators, this is not me telling you to go out and subscribe to a platform. I’m just saying that you really need visual literature in your libraries. ASAP. And if you’ve not started yet, going digital is the quickest way to fill that gap.

I also provide visual literature recommendations every single month for schools. So, for any librarians in my network who receive the Comics Plus Reading Challenges from JCS: hi! That’s me. And yes, I’ve read everything I recommend.

If you’re looking for general tips on how to support those who struggle with traditional reading (neurodivergent or not), I think there are three fundamentals:

- For schools, try and provide a range of different types of literature. Just one story can get someone hooked.

- Don’t shame us for our reading choices. Instead, try to celebrate it. And, above all else, do not negatively compare our choices to those of our peers.

- Make discussing reading a social joy, not a social anxiety. Ask us to explain why we like certain titles and get us talking about them. This is great especially if a piece of reading relates to a special interest.

Also, a shoutout to JCS for being the first full-time workplace to accept and cherish my autism, even if it meant redecorating my desk at work in pink.

Ellie Lathbridge joined JCS Online Resources after graduating from her Master’s degree in Classics from University College, Oxford. Having fundraised her way through her postgraduate degree online and working to provide application mentorship for minority ethnic groups, Ellie is passionate about how digital resources can be used as life-changing tools for educational accessibility. Outside the office, you can usually spot her at the theatre, baking a fresh batch of cookies, or at a life drawing class. She’s also an avid quizzer and board games enthusiast – she’s even won Pointless!

We curate high-interest, immersive digital content that helps schools and libraries expand and diversify their collections—without breaking their materials budgets.

We curate high-interest, immersive digital content that helps schools and libraries expand and diversify their collections—without breaking their materials budgets.